Leisure & Culture #25

The Bright Mountain at the End of the Grove

Dixon

Written by Kit Chan

Translated by v_P

Photos by Kit Chan

Dixon still remembers his summer holidays four years ago - just when he finished the nightmarish public exams, he was up for another challenge. “My teacher asked me to sit down, and handed me a dish: trim this up, then we’ll talk.”

“Trim up” is jargon used in the porcelain painting industry, which means holding a dish (on one hand) while handpainting its trim with a writing brush.

Dixon was 16 years old then. He loved painting and was determined to learn the art of Guangzhou Gilt Hand-painted Porcelain, so he went for the most famous Yuet Tung China Works. Founded in 1928, it was the first, and is now the last, remaining factory of its kind in Hong Kong. Its star-studded list of clients once included governors, five star hotels, and aristocrats from all over the world.

Dixon’s first try didn’t go well, so he wiped it out to repaint it. One of the craftsmen inspected his work and told him, “Come again anytime if you want to learn.”

That craftsman was Mr Chi-Hung Tam. Painting porcelain in Yuet Tung for 46 years, he is the only craftsman left in the factory who knows how to fully paint this style of porcelain by hand.

From then on, Dixon became his apprentice, visiting the porcelain factory at least once a week to learn the craft and closely observing how his teacher worked. Mr Tam would also assign him homework, giving feedback and amendments when he handed them in.

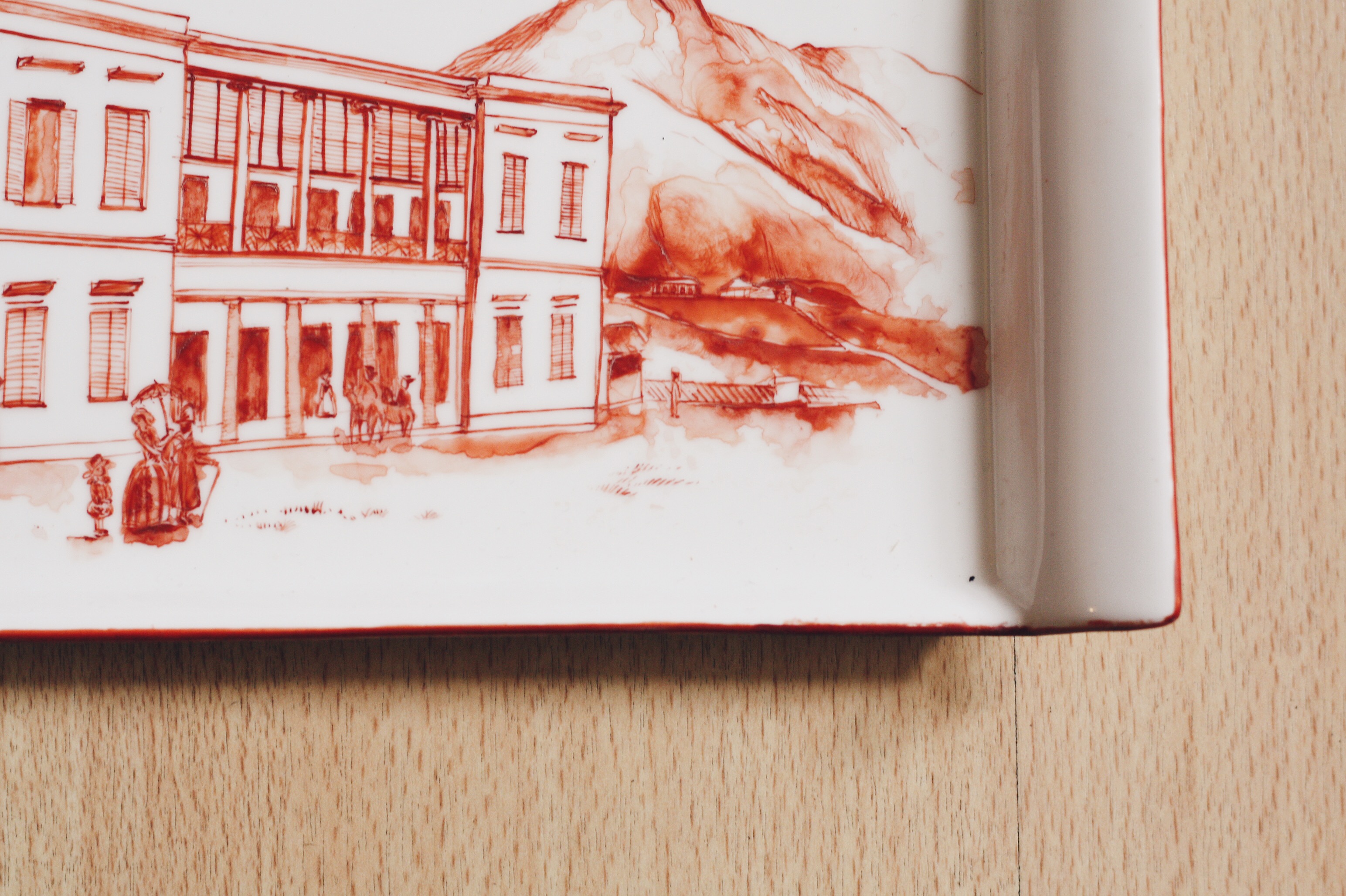

Like Dixon, many more came to Yuet Tung to learnt the art of painting, but Dixon was the only one with perseverance. Four years later, the Form 3 student grew up to be a freshman at his university’s Faculty of Design. Besides classic patterns such as roses in medallion, fighting cocks, flying dragons, and drifty clouds, Dixon added sketches of Hong Kong in the old craft, such as plans of public housing, the Bank of China, Cheung Chau Bun Festival, and also referred to old pictures to repaint the bygone Victoria city.

Using only blue and red ink on white porcelain, he warmly nicknamed his work after the popular nylon bag design: Red White and Blue.

He held an exhibition at SOIL, a little shop that promotes local handcraft, as the apprentice’s attempt to open up another door for the old craft.

Dixon also enjoys the long lost bond of apprenticeship. When he is not painting, he moves stuff and runs errand for Mr Tam, smoking and taking walks together. Dixon is willing to do so, as his teacher taught him everything about hand painting, for free.

“My teacher is quite lenient towards me, the professors in university are what you would call mean!” Dixon laughs. “At least he won’t tell me to give up, ‘forget about it’!”

He is indeed the lucky one. As Mr Tam recalled, “it was hard to learn Guangzhou style porcelain in the old days, the old craftsmen were so unwilling to share, if you stepped in any closer, they would immediately put down their brushes.”

Dixon even got to try his hands on the precious “black glaze,” a fine black porcelain ink that has ceased production. All Yuet Tung had left was half a small bottle of it, and it was only at Mr Tam’s disposal.

“It is equivalent of a 0.05 technical pen, capable of drawing out the finest line,” Dixon’s eyes shine with glee as he explains. “My teacher doesn’t want me to be a pattern-printer, he insist I should first learn how to draw an outline.”

Mr Tam is a strict teacher indeed: nothing Dixon painting over the last four years was allowed to be sent into the kiln for final production. “He won’t let me keep my homework, I must wipe them all by myself, that’s so crushing!”

Such harshness was not meant to achieve the perfect craft, as the essence of Guangzhou Porcelain lies in the most unnoticeable difference in the detail. That is not considered a fault, but a vivid touch of the craftsman’s personal style. “If there is no style, and everything is drawn the same, we might as well use a stamp.” Such is Mr Tam’s motto on handpainting porcelain.

Though Mr Tam is half a century older than Dixon, the two share a common interest in dinnerware. As a porcelain painter, Dixon works under the name “the Bright Mountain at the end of the Grove," inspired by a scene described in Su Shi’s poem: at the very end of the groves, you will see the brightness of the mountain. What was meant to be a self-encouragement during his public exams, fit perfectly with his journey to learn porcelain-painting.

“Everyone sees Guangzhou porcelain as the dinosaur, the sunset industry with no future…come on!” This daring 20 year old won’t give up without a fight. “Why are people so sure that there is no way out? As long as my teacher is willing to teach, there is no reason for me to stop learning.”

And Dixon is certainly getting on track: four years ago when he first came to learn handpainting, he could only sit by the staircase or corridors; this year, after years of hard work through a sea of ceramics, he finally earned a seat in the factory, with his lamp switched on, keeping his elbow steady, drawing line by line.

Adress:Soil, S307, 3/F, Staunton, PMQ

Grove Studio:https://www.facebook.com/grovestudiohk

Yuet Tung China Works:www.facebook.com/yuettungchinaworks