Leisure & Culture #41

Reshaping of New Era

Edo-Tokyo Open Air Architectural Museum

Text & photo: Kit Chan

How does the "library" Hayao Miyazaki, the distinguished animation guru in Japan, often visits look like?

Named as Edo-Tokyo Open Air Architectural Museum, the "library" is simply a place comprising a range of priceless historical buildings for study and appreciation instead of a sea of books.

Being one of the very few in Japan, this outdoor museum, a seven-hectare site inside Koganei Park in Tokyo established in 1993, relocates during the past 20 years some historical buildings of high cultural values and of great challenges of conservation scattering around Tokyo. Since the opening of the museum, the number of the rehoused buildings has increased to thirty from thirteen, including cottages, residences, a public bathhouse, a photo studio, a gastropub (izakaya in Japanese) found in the period spanning from Edo to early Showa.

The demolished buildings together with the furniture and furnishings therein are all moved to the museum for repair, reinstallation and most importantly exhibition.

While his Studio Ghibli founded in the vicinity in 1985 witnessed the birth of the museum, Miyazaki expected inspiration from time to time during his stroll along the road. It is no surprise the cityscape in the setting of the movie Spirited Away epitomizes the buildings in the museum, for instance the ceiling-height chests of drawers for stationery items found in the stationery shop Takeisanseido are the clue of creation of the Chinese herbal medicine cabinet of the old hot spring shop owner in the movie.

In return, the mascot of the museum gives credit to Miyazaki because of his design of "Edo Maru" inspired by the frequent appearance of the caterpillar in the movie. The "Ghibli's 3D Building Exhibition" held by the museum in 2014 even showcased in particular the models of classical architecture in the animation and the process of their production so as to enable the movie fans to get a fuller picture of the self-convincing intimate relationship between the real buildings and their virtual counterparts in the movie.

The museum not only nurtures the study of Japanese architecture but also delivers the social significance by exhibiting the authentic historical values of each building without any change of space use and layout settings after relocation. Instead of being duplicated or remodeled, all buildings are reinstalled cultural property presenting the living style of Japanese of a certain period of time and space.

For example, in the Taisho period (1912-1926), Japan saw a surging number of the Western modern architecture spurred by the European romanticism, where among the most remarkable ones was the former residence of Kunio Maekawa, a France-educated contemporary Japanese architect who played an active role in advocating modernist architecture in Japan.

During World War II when there was a serious shortage of building materials, Maekawa gave up concrete and instead made good use of wood, bricks and roof tiles to create a surprisingly groundbreaking masterpiece of a mix of traditional Japanese flair with an exceptionally modern twist by focusing on symmetry, natural light and spatial effect and consisting of a study, a maid's room and a Western bathtub etc.

What lies in the museum area as well is a retail street reminiscent of the Showa era comprising shops selling flowers, hardware, and soy sauce; inns, food stalls. Despite the street repavement, all shops are genuine and truthfully show those years of daily livelihood.

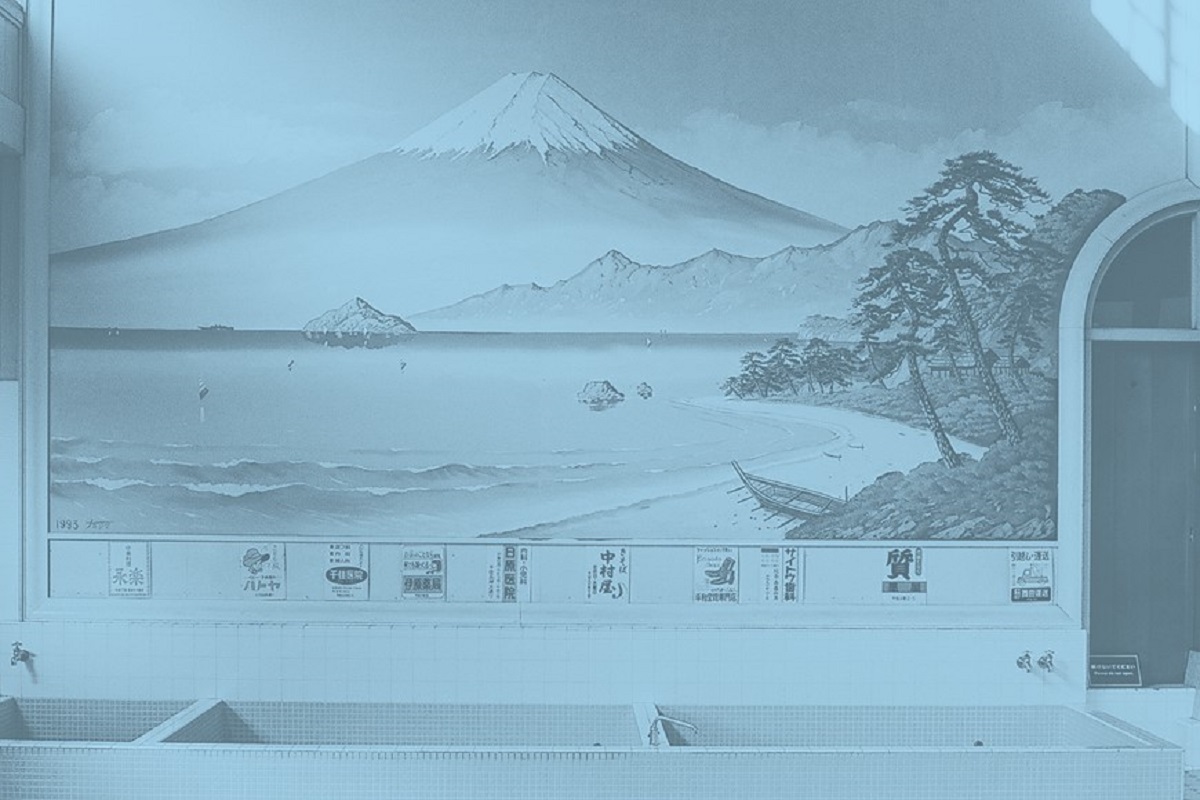

Kodakara Hot Spring is an example. Commencing from 1929, the present photo-taking hotspot finds a sacred Mount Fuji mural painting in the hot spring exclusively for men, but a painting showing the scenery of the middle of a mountain for the female counterpart. This underlying message of overlooking (or expecting) the holy mountain across the high wall highlights the gender inequality of those years.

From the perspective of conservation, relocation and reconstruction of buildings after demolition at the original sites inevitably arouses controversy: will the cultural significance remain without any loss when the buildings are relocated away from access of the previous users and even the history of the neighbourhood?

Undeniably though, in spite of the respective individual relocation, the residences, the florist, the hardware firm and the soy sauce shop remain the testimony of contemporary architectural aesthetics, for further inspiration of the future generations.

The delicate manifestation of eras thanks to the detail-mindedness of Japanese provides a worthwhile demonstration to Hong Kong which is always in a dilemma about conservation and preservation: the respect for an awesome building equals that for the past of a city.

The last to retain is not only the building but also the identity and the persistence in the pursuit of beauty.

Edo-Tokyo Open Air Architectural Museum

3-7-1, Sakura-cho, Koganei City (Inside Koganei Park)