Leisure & Culture #29

Family Rules

Kung Lee Herbal Tea

Written by Kit Chan

Translated by v_p

Photos by Kit Chan

How would a restless teenager react if someone asked him to stay at a tiny shop, selling sugar cane juice for the rest of his life?

“No way!” Man-Chung Chui remembered how he bluntly turned down his parents’ request. “I wanted to have fun and enjoy my freedom.”

He was 16, and just graduated from high school. Not cut out to be an academic, he wanted to follow another dream: to be a professional bartender. “It’s so cool to be a bartender, you get to meet people, and it’s easy to get girls too,” Chung said honestly.

His family business isn’t a bar, but the historical Kung Lee Herbal Tea Shop at 60 Hollywood Road, Sheung Wan. Opened since 1948, it was founded by a landowner called Mr. Lam, who had sugar cane fields at Yuen Long. After three generations, the shop is now owned by Chi-Sun Chui, with Chung being his eldest son.

How could a 68-year-old shop keep a kid from the world outside? Chung worked in bars, karaoke, Japanese restaurants. He became a bartender as he wished, met people from all walks of life, and had lots of girlfriends too. But after a few years, he grew tired of all this. “Every place is the same, and everyone does the same things in clubs, that is to drink until 3, 4 o’clock, and come back again night after night.”

Seven years ago, his father persuaded him again to help out with the family business, and he finally said yes. “I thought I’ve been there, done that, it’s time to settle down… as Dad is getting older.”

He took over the business reluctantly, just like his father did 30 years ago. Born in Guangzhou, Mr. Chui was 16 years old and just completed junior high when he came to Hong Kong. He worked for a relative who was the second owner of Kung Lee, but got bored after a few years.

Eager to make his mark, he tried working in an electroplating factory and as a roaster in a Chinese restaurant. By the year he got married, his relative decided to retire. With no one to care for Kung Lee, Mr. Chui hesitantly agreed to take over business at 27 years old - exactly the same age when his son decided to come home.

Like father like son, they made the same choice at the same point of their lives.

Located in a pre-war building, the family lives upstairs from Kung Lee, and starts their day downstairs, everyday. As monotonous as it sounds, Chung gradually realized there is so much to learn from a cup of sugar cane juice.

For example, it is considered a normal practice for other shops to extract juice from unpeeled sugar cane to save time, and even soak the sugar cane in sugar water, to make it sweeter.

But Mr. Chui insists on following the rules set out by the founder of Kung Lee 68 years ago - to do it by tradition. That is to peel the sugar cane skin before extracting the juice, and simmer it slowly for two hours.

“Raw sugar cane has a grassy smell, the juice would be fresher and sweeter if cooked, and healthier to digest too.” Mr. Chui explained. Furthermore, only green skinned sugar canes are used, instead of black skinned ones, so that the juice would be sweet and clear.

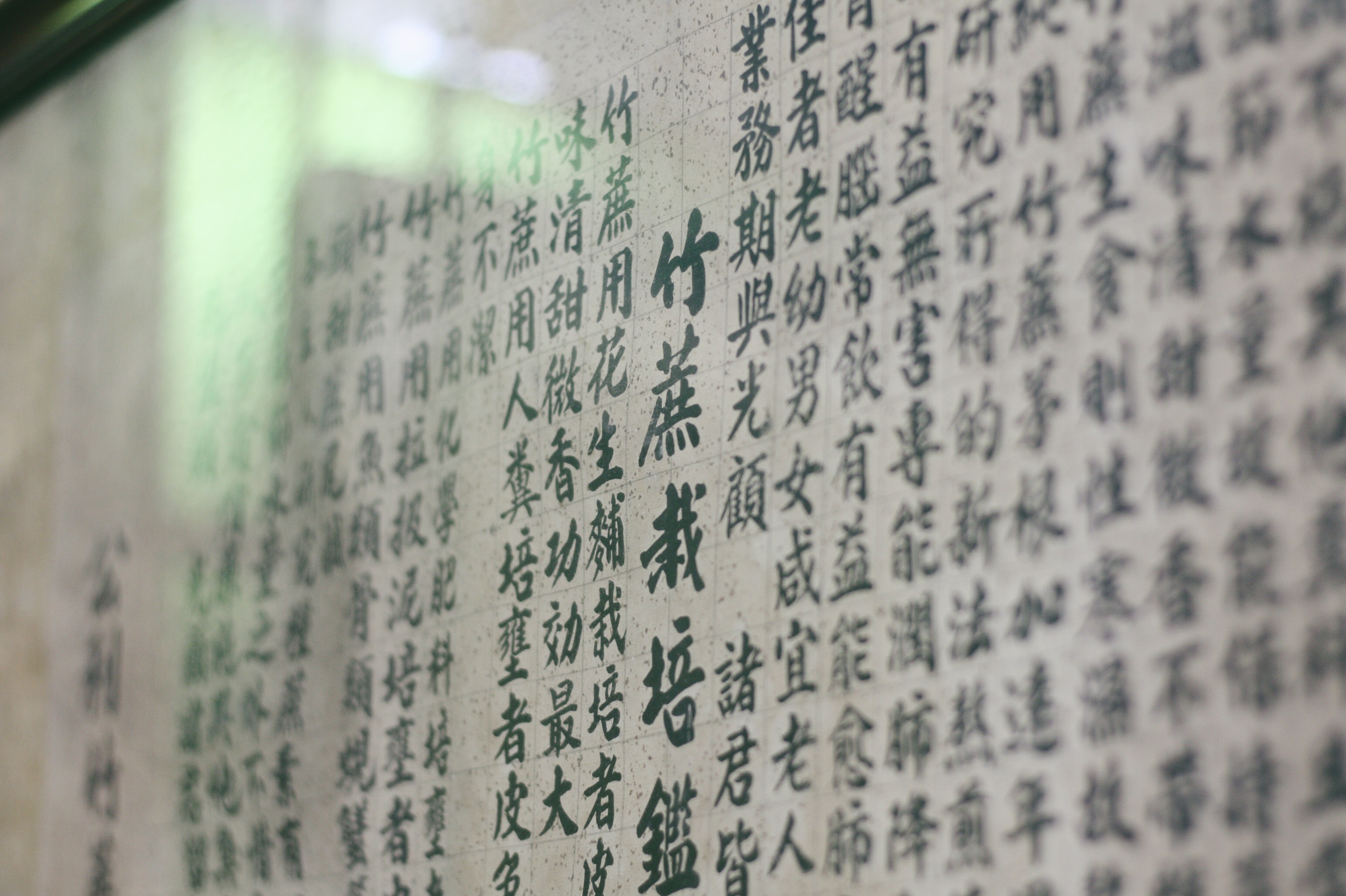

Tradition was based on respect for the one who started it all. On the flowery walls of Kung Lee, are guidelines on “Sugar Cane Planting and Identification,” which specifically required sugar cane be fertilized not by human waste or chemicals, but only by peanut bran, to guarantee a sweet and good crop.

Originally written by the founder as a customer guarantee, it became the golden rule for Kung Lee, guiding newcomers for half a century to make “the real deal” with the best materials and method possible, for “the public good”, as the shop name suggests .

Like the trees growing along the walls, the family business has stayed long enough to witness the crazy changes happening around its neighborhood.

“There used to be a lot of shops selling sugar cane juice in Central.” Mr. Chui recalled how he saw them close down one by one, with the last one just a minute away from his shop, right across from PMQ (the former Dormitory for the Married Police), which also closed 10 years ago. From then on, the only one left in the Central West area was Kung Lee.

“No shop owner would want to face closure, usually it’s their children who don’t want to take over.” Chung became more nostalgic as he grew older. “If tradition dies out, young people won’t know what Hong Kong used to have.”

Recently, young cultural hipsters are seen taking pictures with the “poster boy” hand-painted on the stone pillars at the entrance, who resembled the looks of pop singer Leon Lai.

“The poster was here since the early 80s, drawn by an art student under the boss’ request to promote their new product: the turtle jelly (Guilingao). Ads were all hand-painted in those days.” Mr Chui laughed with amusement. “Leon Lai wasn’t even a star yet.”

The young crowd may not be aware that back in the 1960s and 70s, shops like Kung Lee were “hip” places to socialize and a “pharmacy” for the poor, who would come and drink a cup of herbal tea to cure their ailments and sore throats, instead of seeing a doctor.

Nowadays, Chung’s younger brother, a Design graduate, also joined forces with his brother and father, the three of them holding on to the family business, and a common city landscape worth treasuring.

Kung Lee Herbal Tea