Leisure & Culture #69

From “Double-boiled Soup” to OmniPork Luncheon — About City Culture

Written by Tinny Cheng (Founder of The Culturist; Owner of Tai Yip Art Bookshop)

Photos: PMQ, Online images

The stars are not culture, constellations are. “And afterall, culture is the values created by human beings, which guide our way of living.” said Louis Yu, an experienced art administrator in Hong Kong.

It reminds me of the Roman philosopher, Marcus Tullius Cicero, who, for the very first time in 1 BC, coined cultura anima—cultivating soul. What a poetic sense of mission.

Since culture is man-made and human come in many different styles, looks and cultures may vary in different places. “Imagine a city as a pot of soup, put in ingredients, give it time to simmer and we shall have very different flavours.” In 2019, Louis Yu stepped down from his position as Executive Director, Performing Arts at the West Kowloon Cultural District Authority. He then went to the London School of Economics and Political Science and furthered his research on Urban Study, carrying with him luggage and a question. After twenty years of struggle, the West Kowloon Cultural District that Yu played a large part in propelling finally opened. Viewing the majestic mega-structure, the question in Yu’s mind rang again: “Now that the hardware is built, is our city becoming more cultural?”

“Imagine a city as a pot of soup, put in ingredients, give it time to simmer and we shall have very different flavours.”

Values + Living + Arts + Memory + Space = City Culture

Yu’s classmates included an ex-mayor in Brazil, a senior manager in an international bank and a commissioner of the Philadelphia Fire Department. They were all deeply interested in the relationship between people and society. During the semesters, he went to 14 European countries where he had never been to, contemplating the very question. In the end, hoping to create a relatively objective measuring system of culture, he came up with BEAM, an index to measure city culture. The combination of Belief and Value, Everyday Life, Arts and Creation, Memories (B-E-A-M) and the notion of Space became the system of a city culture. In other words, the above elements define the character and the significance of a city.

So is it a long-simmered Chinese soup with watercress, dried duck kidney and pork tendon? Japanese miso soup? Thai Tom Yum Soup? Spanish Gazpacho? Or Italian Pappa al Pomodoro? City cultures are as vibrant as soups. Be it cold or warm; sweet, sour, bitter or spicy, soup sources from its land (and water) and distills from the living habits of its people. It works the same way for cities. Be it intellectual, gentle, business-oriented or knowledge-based, every city radiates its own colour.

In the internet age, cultures mix, distill or ferment into new tastes and colours. “In Hong Kong, for example, Korean pop culture has been brewing for twenty years and Christian culture has been simmering for 120 years. They both evolved into their own distinctive style with a touch of Hong Kong-ness. And, they keep evolving still.”

Early May at PMQ, the historical architectural cluster, Yu presented his cultural concept to fellow cultural practitioners.

Yu returned to Hong Kong in the midst of the pandemic. From a full-time student, he rose to be a preacher of culture, organizing over twenty seminars titled What Makes a City Cultural? where he met various people online and face-to-face to promote the idea of BEAM. He is also planning to refine and broadcast his evangelist campaign through the internet, radio and more meetings, hoping it will take root. Early May at PMQ, the historical architectural cluster, Yu presented his cultural concept to fellow cultural practitioners.

He explained that the Central and Western District, in which PMQ is located, is among the top three areas with the highest BEAM index, coupled with a racially diverse population and a high number of monuments, religious sites, Intangible Cultural Heritage, galleries, education institutes and restaurant licenses. “Because the place is a product of 19th century urban planning, which was designed to be concentrated and mixed-use.” In his view, the conservation project PMQ provides complementing cultural significance.

Central and Western District, in which PMQ is located, is among the top three areas with the highest BEAM index, coupled with a racially diverse population and a high number of monuments, religious sites, Intangible Cultural Heritage, galleries, education institutes and restaurant licenses.

Culture is an ideology of collective fermentation

“When Netflix’s human resources department is named Culture Deck rather than HR, you should have realized in our society, what kind of ideology has culture transformed into.” In Yu’s opinion, culture is a kind of collective fermentation. Without documentation and memories, a culture cannot be consolidated and gained mass. “The heavier the memory, the longer it can pass on.” He shared how he was deeply touched upon seeing a collection of combs from across the centuries at Museum of Ethnography in Sweden. Black hair turns grey year by year—and every comb is a story.

Culture changes a city’s lifestyle, economies and even eating habits. Louis Yu pointed out that the recent OmniPork Luncheon is an inspiring example of an ideal-driven, mind-changing and creative marketing plan.

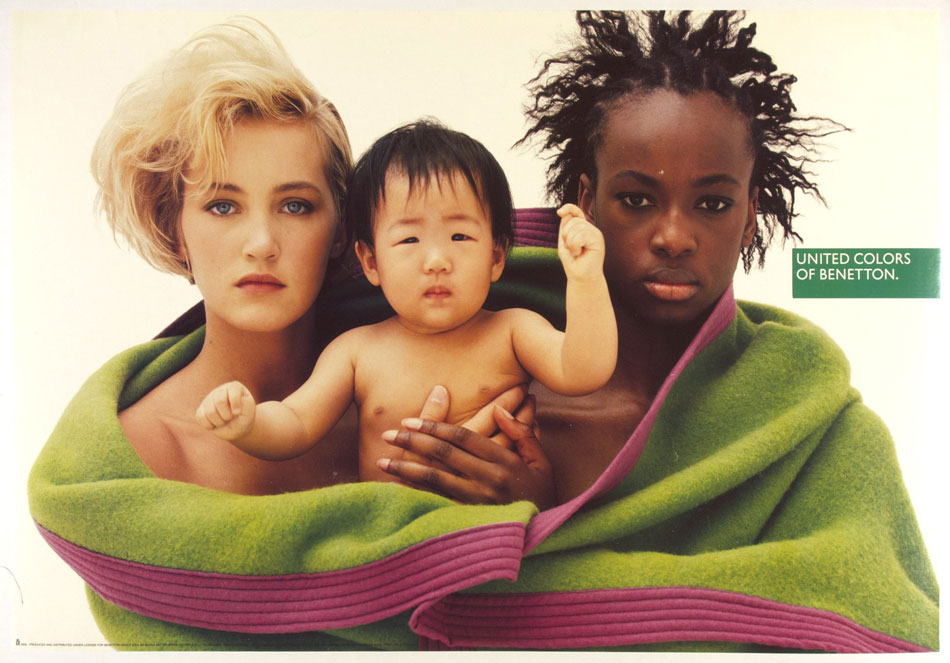

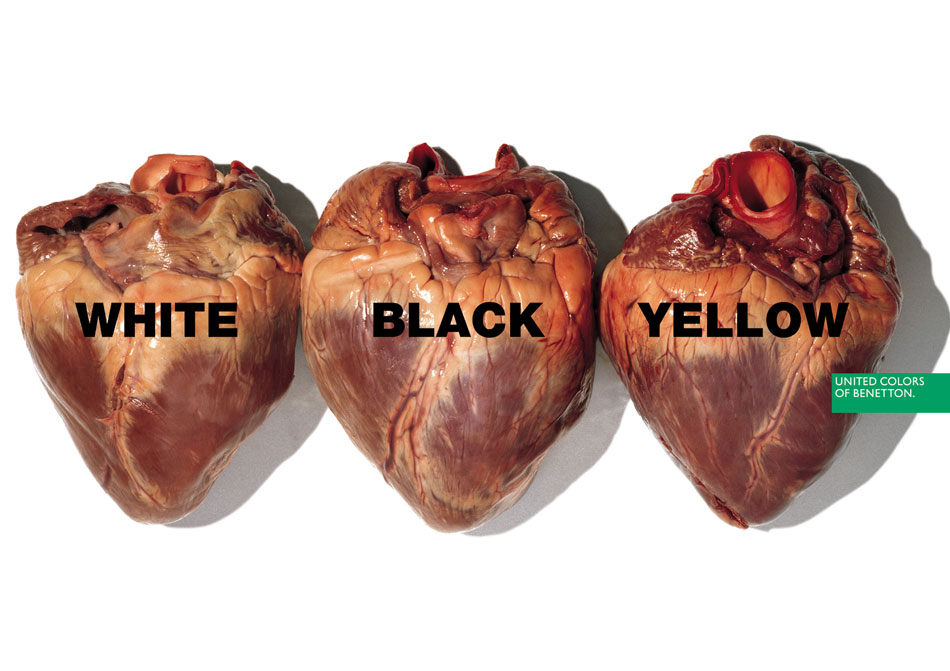

“Hong Kong people are gross. Spam is high in sodium, fat and calories. We have it for breakfast. However, this plant-based meat production company chose to put the ‘evil food’ first in line, using it to propagate healthy lifestyle, animal rights, and being environmental and religious friendly. Young people are likely to buy into the humanitarian idea.” In the 80s, Italian photographer Oliviero Toscani created for the once-popular brand Benetton a series of provoking advertising shots, calling for actions against racial discrimination and wars. It turned out to be a world-wide success, breaking cultural barriers and branding Benetton as the “bad boy” in fashion.

In the 80s, Italian photographer Oliviero Toscani created for the once-popular brand Benetton a series of provoking advertising shots, calling for actions against racial discrimination and wars. It turned out to be a world-wide success, breaking cultural barriers and branding Benetton as the “bad boy” in fashion.

Yu recalled that brands that ran on beliefs have traditionally targeted the middle-class. “By contrast, OmniPork has made a risky move to walk into wet markets and majority households with their ideals, attempting to create a belief economy,” he said. If a popular culture cannot transcend to a classic one, he believes that its scope of influence will be limited and there are many historical examples. “In ancient China, some cultures only affected commoners, but not scholar-officials. In turn, they could not receive certain resources and attention, and failed to become a part of public resources. It applies to the present too," Louis Yu said.

His conclusion is succinct: “If a place only produces new things, without properly respecting and documenting its memory, its culture will be weightless, for culture is not a trend.”