Design Feature #16

Authenticity In The Age Of Mechanical Reproduction

Goods of Desire // Muji // Monocle

Written by RMM

Photos by Goods of Desire // Muji // Monocle

When Goods of Desire (G.O.D.) burst onto the Hong Kong retail scene in the late 90s, it made culture cool and consumable. Using “quintessentially Hong Kong” imagery and cultural quirks, G.O.D.’s products infuse humour and creativity into everyday objects.

‘Red Lantern’ lights // ©Goods of Desire

‘Rattan’ soap dish inspired by 1970s rattan chairs // ©Goods of Desire

Objects such as the red lantern lights, rattan motifs, metal mailboxes, and plastic slippers are iconic, familiar items from any Hong Kong resident's childhood. This unique cultural legacy has now been adopted, not only by G.O.D, but also other retailers, as a means to suggest their authenticity and sense of nostalgic establishment.

While everyone is trying to ‘keep it real’ with these nuggets of culture, it’s easy to forget that this authenticity is mass-produced to be consumed by a largely international audience.

What is authenticity anyway? Shakespeare probably said it best when he wrote “This above all: to thine own self be true.” Authenticity at its very core, looks back at our past while moving into the future. So in a way, these cushions are in pursuit of authenticity. They reference a collective past, but also embrace a desire to reinvent its form and function. But in the age of mass production, mass consumption and endless reproduction, we should look beyond the function of the object. Authenticity is about the intention that an object was bought and sold with.

"2004 Muji Wano Syokki-Teaset Mug Masahiro-Mori" by 森正洋デザイン研究所 (Mori Masahiro Design Studio, LLC.). Licensed under CC BY 3.0 via Commons.

Which brings us to brands like MUJI and Monocle, which occupy a unique space where mass production and interpersonal, cultural communication converge. These brands try their best to de-emphasise the industrial nature of their production (factory-produced for MUJI items, and large print runs for Monocle).

MUJI Hot Water Bottles // Designed by Yotaka Kuda and Go Kimura // Photo by Chihaya Kaminokawa

Let’s talk about MUJI first. As a brand, MUJI has a middle-class image and its natural, simple and anonymous design harkens back to a simpler time where function and practicality preceded over-the-top design. It eschews frills and extras, and all its products radiate a simplicity that can only be achieved through complexity of thought and design. The brand is authentic of course, with respect to how it aspires to not only be modest and plain, but to be as ubiquitous as possible.

But there lies a contradiction, as the late cultural theorists Theodor Adorno and Max Horkheimer suggest, when speaking about how industrialisation has robbed people from their authentic culture.

Mass production makes everything homogenised.

If they were alive, Adorno and Horkheimer would contend that MUJI’s industrially reproduced and ‘designed culture’ only allows people to consume mindlessly, because true authenticity always leaves room for independent thought.

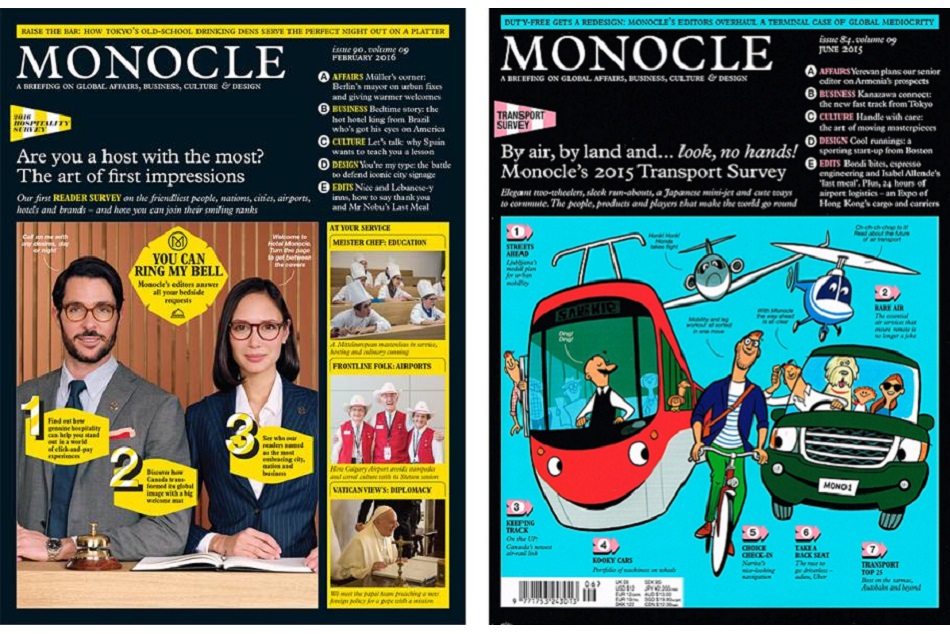

Monocle Magazine (Illustration by Satoshi Hashimoto)// ©Monocle Magazine

This struggle to remain authentic amidst a structured, designed culture can also be seen in the magazine, Monocle. As a publication, there’s no denying that it’s well designed. Each issue is made up of over 300 pages of uncoated stock, nestled within often vibrant and glossy covers that are unquestionably quite wonderful to hold in your hand – especially if you’re a well-heeled, sharply dressed sophisticate.

This same slick, tailored approach is echoed through its content as well. Monocle’s obsession with creating an attractive, livable city permeates issue after issue. Like how MUJI simplifies everyday objects to their bare bones, Monocle’s attempt at selling their vision of a modern and authentic city life, is often achieved by simplifying the complexities of urban planning.

There is no problem Monocle’s editorial team can’t solve without cheerful illustrations drawn in an uncomplicated style, or intimate portraits of small business owners lit impeccably with natural lighting. Never mind that this honest, optimistic lifestyle is neigh unaffordable for many of its readers, but more importantly the 99% who are supposed to benefit from their nifty solutions.

Cities, we remind ourselves, should be for citizens and not consumers.

So the next time you pick up a copy of Monocle or a product from MUJI, stop before you give yourself a pat on the back for being an individual who only buys from ‘authentic’ brands. Can the brands you buy from, even with their warm and hopeful promises, truly be authentic if you’re only one of the 77,030 readers or part of a 260,000 million yen revenue?

Official website: